What is the world’s oldest animated film? Or rather, knowing film history–what’s the world’s oldest surviving animated film? Many sources will point to the cartoon Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906) or “trick film” The Enchanted Drawing (1900), which used stop motion to make a cartoon face change expressions. But chances are you might’ve stumbled across a few sources making the case for an obscure short called Matches: An Appeal–said to have been produced in 1899.

It’s a pretty cute little film, too. Via the magic of stop motion, two small figures made of matchsticks work together to write an “appeal” asking the public to donate money to send matches to needy soldiers. To be precise, they write: “For one guinea Messrs Bryant & May will forward a case containing sufficient to supply a box of matches to each man in a battalion with the name of the sender inside. N.B. Our soldiers need them.” The stop motion is surprisingly sophisticated for its early date–perhaps a little too sophisticated.

Time to fall down a research rabbit hole! Always one of my favorite hobbies.

First, what do you think?

So! The story goes that British animator Arthur Melbourne-Cooper (who worked for Birt Acres and later made charming stop motion films like Dreams of Toyland) was commissioned to make the short by match manufacturer Bryant & May. The matches were for soldiers fighting the Second Boer War, which began around 1899. Yes–the Boer War. Now that’s awhile ago!

Arthur and Arthur’s magnificent ‘stache.

Charmed by this little-known short’s pragmatic purpose during a fairly obscure war (the World Wars get all the spotlight nowadays), I did a little reading and found out that not only is the 1899 date in question, but, there’s also an ongoing controversy about Melbourne-Cooper! Some historians feel he’s been unfairly overlooked and was actually the true creator of some of our most famous ancient films. Allow me to explain, somewhat briefly.

The first person to champion the Melbourne-Cooper cause was his daughter, Audrey Wadowska. In the late 1950s, when her father was in his 80s, she went to a film history exhibit and became convinced that a group of early films attributed to George Albert Smith contained shots of her relatives, which would therefore make Melbourne-Cooper the more likely creator. She began searching for documents and memorabilia relating to her father’s career, determined to write his life story and restore what she felt was his rightful place in cinema history. I turned up a couple newspaper clippings about her, such as this one from the British tabloid The Daily Mirror:

Daily Mirror, Feb. 21 1958.

The early films in question were six shorts including The Little Doctor (1901), As Seen Through a Telescope (1900), and the famed Grandma’s Reading Glass (1900) (which contains the world’s oldest closeup). Wadowska became very dedicated to her cause, giving lectures and creating an archive of her father’s material (which is currently in Rotterdam).

Soon more researchers were championing the “wronged Melbourne-Cooper” cause, most notably Dutch historian Tjitte de Vries (he even co-authored a 570+ page book about him!). The debate heated up in the 1990s with a whole series of articles in the film journals KINtop and Film History, where arguments for and against the obscure British filmmaker flew like ping pong balls. One that I found enlightening was the 2002 Film History article “Smith versus Melbourne-Cooper: An end to the dispute” by Stephen Bottomore, which gives a strong case for George Albert Smith being the rightful filmmaker after all. Bottomore points out that much of Wadowska’s evidence relied on reminisces from family and friends, which is grand and all, but not super objective. (I agree.)

Probably not related to Arthur.

So how’s this all related to the contested 1899 release date of Matches: An Appeal? Well, if Melbourne-Cooper was an active and innovative filmmaker around 1900-01, it would seem to make the 1899 date more plausible. However, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that he became an independent filmmaker until about 1906, and it’s likely the poor maligned George Albert Smith made the 1900-01 films mentioned earlier. And since the animation is very sophisticated for 1899, it’s possible the “Appeal” was made during WWI. Indeed, many historians–including the BFI–peg 1914-15 as the more believable time frame.

Personally, I feel that since more archival material is available online than ever before, it should be easier to lay some of the Arthur Melbourne-Cooper arguments to rest–and perhaps find some clues to the Matches mystery. If I might humbly throw my amateur historian hat somewhat near the ring and make some very cursory sweeps through the Interwebs, I can report:

Searching the online film magazines and trade journals on Media History for “Melbourne-Cooper” with the dates limited to 1895-1930 brings up a grand total of: 2 results. (So does “Melbourne Cooper” sans hyphen, mind you.) For comparison, “Melies” brings up a whopping 3223 results. On newspapers.com, whose search engine is dumb and needs you to be more specific, I looked up “Arthur Melbourne-Cooper” from 1895-1930 and found zero matches. “George Melies,” on the other hand, has 121 matches.

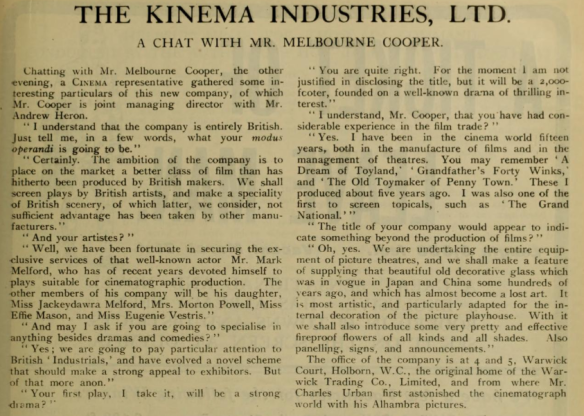

In fact, the only solid thing I found was this 1913 interview with The Cinema News and Property Gazette:

The Cinema News and Property Gazette, March 19, 1913.

Notice he doesn’t say “I was also one of the first to specialise in stop motion photography” or something like that.

All very cursory, mind you. Maybe you’d retort that since Melbourne-Cooper was British, British archives are sure to be bulging with clippings about him. Alrighty, let’s see what the British Newspaper Archive has for us:

(My search did capitalize his name, by the way. BNA likes lowercase, I guess.) Now, I haven’t look through many British cinema trade journals, but my guess is the results may be similarly paltry–I could be wrong!

Which all doesn’t prove that Melbourne-Cooper wasn’t important in retrospect–just that in his time he seems to have been a minor figure. If historians did overlook his accomplishments, it wasn’t a case of taking a famous name and trying to sweep it under a rug (for murky reasons).

Arthur’s ‘stache is relieved to hear that.

Regarding Matches: An Appeal itself, searches using numerous stop-motion-match-related terms yielded another big fat zero. Of course, it’s anyone’s guess whether this little film would get many mentions in periodicals, or if I just don’t have access to the right ones (forgive my cursory-ness). Some sources say the film was shown at The Empire Theatre in London in 1899–at last, something specific! But as of right now, being all cursory and all, I’m not sure where this piece of info comes from. (Likely Wasowska or de Vries.)

I’ve come to the conclusion awhile ago that when in doubt, scrutinize the film for clues. To me, the only thing about Matches: An Appeal that seems a tad 1899-ish is the background. Why not face the wall full-on? Did the film maybe begin with the matchstick figures walking through that door? If it’s scaled to matchstick size, are the little figures supposed to be children-sized? It’s the sort of thing that seems primitive, I guess–but not that much, really.

No, the major clue in Matches: An Appeal is the writing on the wall. Let’s look at it again:

“Our soldiers need them.” Now, I don’t know much about the Boer War, but I do know that appeals for the public to send supplies and small gifts to soldiers were common during WWI. Another pedantic detail strikes me–you often hear about “battalions” fighting on the WWI front, while the Boer War seemed to be all about “regiments.” Maybe the multitudes of Boer War experts out there are laughing right now, but it’s a thought.

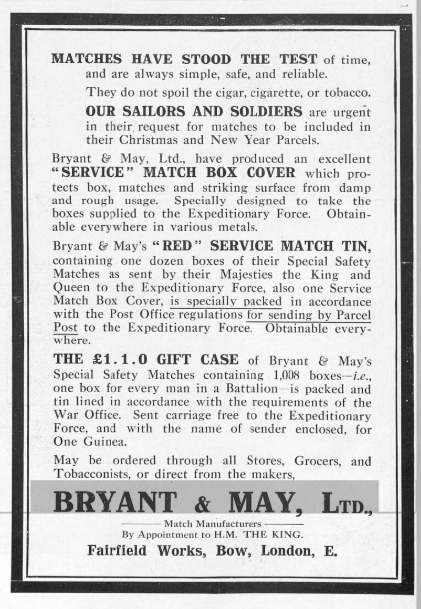

Bryant & May are the real star of the film–any clues there? The company was a major producer of matches for decades (and, err, the cause of the matchgirl strike of 1888. protesting poor work conditions and the risk of “phossy-jaw”). While looking through newspaper archives, I found examples of this ad from British newspaper The Sphere:

The Sphere, Dec. 16, 1914.

Some of the wording’s pretty similar to the writing in Matches: An Appeal, no?

Here’s another ad from London’s The Observer:

The Observer, Dec. 20, 1914.

The WWI time frame is starting to look better and better. The same Observer contains a brief article about the matches drive:

The Observer, Dec. 20, 1914.

Now, this may be just a hunch, but if I were an Arthur Melbourne-Cooper historian I’d start checking around to see if a marvelous new trick film with charming matchstick figures was shown in any British theaters around Christmastime in 1914.

So yes, I’m thinking 1914 makes far more sense for Matches: An Appeal than 1899–just based on this bit of research, cursory-style.

One last tidbit: the research waters have been somewhat muddied by the existence of a film called Animated Matches (1908), thought to be another one of Arthur’s whimsical matchstick creations. Nope, it’s a Gaumont production, and involved a box of matches rather than human-like match puppets.

The Nickelodeon, Jan. 13 1909.

Someone get that off Arthur’s IMDb page, please!

The reasons for research controversies like these are legion, but the main ones definitely involve attraction to the idea of authorship and the desire to see justice done to forgotten names. And perhaps, there’s also a buried desire to receive glowing credit for the justice-doing. Suffice to say that sometimes, certain things can look a little too good to be true.

—

Sources:

My main source for Silent Stop Motion Month is the wonderful book A Century of Stop Motion Animation: From Melies to Aardman by Ray Harryhausen and Tony Dalton. Other sources:

“A Chat With Mr. Melbourne Cooper.” The Cinema News and Property Gazette, March 19, 1913, page 57.

Bottomore, Stephen. “Smith versus Melbourne-Cooper: An End to the Dispute.” Film History 14, no. 1 (2002): 57-73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3815581.

Leslie, Esther. “They Thought it Was a Marvel: Arthur Melbourne-Cooper (1874-1961), Pioneer of Puppet Animation by Tjitte de Vries and Ati Mul (review).” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 43 no. 2, 2013, pp. 78-80. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/524260

Arnold, A.J. “‘Ex luce lucellum’? Innovation, class interests and economic returns

in the nineteenth century match trade.” University of Exeter, 2004. https://business-school.exeter.ac.uk/documents/papers/accounting/2004/0406.pdf

Hmm, what a mysterious mystery. And a nimble bit of research on your part—nicely done! I think you have it pegged—1914 seems about right. It just doesn’t have that 1899 “look” to it, somehow.

Oh thank you–when you get those hunches, you gotta fall down that research rabbit hole!

In 1899, you basically get filmed plays, documentaries, and simple stop-action tricks by Melies. Whipping out that level of animation is like having Marvel movie-style CGI pop up in the 1980s. It just…doesn’t. And can’t!

OUTSTANDING!!!!!!

I’m re-dating my clip of it, you’ve convinced me!!!!!

A debate that has raged for decades…..solved here on our little corner of the internet.

Isn’t there an award you can get or something? FANTASTIC research.

Aw! Of course, it’s not proven until we can find solid evidence of when it was in theaters, but these clues just might narrow the field from “possibly shown anytime between 1899-1920” to “possibly 1914.” 🙂

Brilliant article! It seems like the mystery is solved!

Why thanks, it seems like a logical conclusion to me!